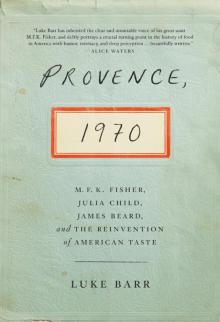

Provence, 1970 Read online

Page 9

Beard wanted this “moral victory”; there was no doubt about that. His weight problems were far from an abstraction, moral or otherwise: He felt terrible, worse than he ever had before. He was having trouble walking, and his legs were swollen and discolored. He was short of breath. But losing weight, he knew from long experience of failing at it, was hard. Success required superhuman self-discipline—not an area he excelled in—and there was the additional problem that his lifestyle was also his livelihood. Food and drink were what he did. Dieting, for Beard, was an existential problem.

Sixty pounds—that’s what Pathé told Beard he needed to lose.

The doctor explained the principles of the diet he had devised for Beard. It was called the “Prudent Diet” and contained a total of two thousand calories per day, and no added salt or sugar was allowed. During the course of his stay at the clinic, Beard was meant not only to acclimate his body to this new diet—to eat half the amount he normally did—but also to learn to plan correctly balanced meals for himself once he returned home. Pathé handed him a sheaf of papers outlining various acceptable breakfasts, lunches, and dinners, along with detailed rules about what he must and must not eat. And drink: the doctor insisted he give up alcohol of any kind, and instead drink large quantities of noncarbonated mineral water.

Of course, for the time being, he didn’t need to think about any of this. He just ate what they brought him. It was never enough.

Breakfast:

70 grams fruit

30 grams biscuits

10 grams butter

Tea

Lunch:

30 grams biscuits

10 grams butter

250 grams grilled tomatoes

150 grams leg of lamb

60 grams brown rice

140 grams fruit

Dinner:

30 grams biscuits

10 grams oil

150 grams cold chicken

100 grams steamed potatoes

150 grams artichokes

140 grams fruit

Everything was carefully weighed and excruciatingly bland. The portions were small: 150 grams of lamb and 60 grams of rice sat on the plate ever so primly, more symbols of food than food itself. A few bites, and they were gone.

There was some variation, but not much. Some days he got fennel or celery instead of tomatoes, or grilled steak instead of lamb. The second week, he convinced Pathé to replace the biscuits with a slice of bread, which was a slight improvement. But the diet was draconian, and it was hard to imagine eating this way permanently, when he wasn’t locked away in a clinic.

For one thing, he was always hungry. For another, there was no wine.

As Beard sat alone in his monastic room in Pathé’s clinic, he looked over his manuscript. He was nearing completion, at long last, of his ambitious book, American Cookery. It would be the definitive statement on American cooking—the culmination of his years as the dean of the American food scene, a celebration of national heritage. He wrote his first cookbook, Hors d’Oeuvre and Canapés, in 1940, and much had changed since. Cookbook writers in the previous decade, and Julia Child in particular, had done much to popularize sophisticated cooking. But “sophisticated,” in the popular imagination, still meant “French.” His was the book that would codify and elevate the homegrown flavors of American food. He had collected recipes from many different sources. He had pored over two centuries’ worth of recipe collections compiled by ladies’ aid societies, missionary and hospital volunteer groups, and women’s exchanges all across the country. He had looked to the legacy of the millions of immigrants who had arrived on U.S. shores from Europe and Asia to trace the evolution of the nation’s cooking. He had even embraced what he called the “Polynesian school of cookery, a combination of American, Hawaiian and Oriental, popularized by Trader Vic and his imitators.”

But it was the food of his own childhood that was most important to him. Beard had grown up in Portland, Oregon, and had an enduring love for the Dungeness crabs, razor clams, mussels, salmon, and trout of the Pacific Northwest. His mother, Mary, was a talented and opinionated cook—she owned a small residential hotel before she was married, and entertained often—and so was Jue Let, the Chinese man who ran the household kitchen. It was these two who taught him to cook, and looking back, he saw that they embodied the American culinary story, one of distinct regional traditions, embraced and transformed by generations of immigrants. (Mary was English and had come to Portland to work as a governess in 1882.) Beard’s father was a distant presence; he was a customs official downtown. Beard’s mother took him to spend weekends and summers on the Oregon coast, in Gearhart, where they prepared elaborate picnics and cooked over an open fire at the beach, and ate an endless variety of chowders, salmon, clams, and crabs. This was the food Beard would always love the most, and the new book would allow him to give it the prominence he felt it deserved.

In the book’s introduction, Beard acknowledged that at that moment in time (1972 was the year it was finally published), French cuisine seemed still to be “the goal of every amateur in the kitchen.” Giving credit where it was due, he said that “without a doubt it is a delight to follow the meticulously planned trail of Julia Child … but we should also look into the annals of our own cuisine,” for “we forget what distinguished food Americans have produced in several periods of our history.” Bringing this cuisine to light was the goal of his book: “We have a rich and fascinating food heritage that occasionally reaches greatness in its own melting pot way,” he wrote. “This book is a sampling of that cuisine, and inevitably it reflects my own American palate.”

Beard had collected recipes for everything from creamed chicken à la king to angel food cake. He was a completist, a rigorous historian of iconic American dishes. There were eight varieties of stuffed egg, from Deviled Eggs to Roquefort Stuffed Eggs. There were numerous chowders: Mrs. Crowen’s Clam Chowder, from 1847; Old Western Clam Chowder; Standard New England Clam Chowder; Mrs. Lincoln’s Clam Chowder; and one he labeled My Favorite Clam Chowder. There were eleven recipes for fried chicken, including multiple versions of Southern Fried Chicken; Tabasco Fried Chicken; Bacon Fried Chicken; Maryland Fried Chicken; and Creole Fried Chicken.

He would not be eating deviled eggs, clam chowder, or fried chicken at Pathé’s diet clinic, needless to say. All such delicious, decadent foods were now off-limits. (That favorite chowder recipe contained three cups of light cream. And fried chicken, well, it was fried chicken.)

His dinner came on a tray. He ate a cracker with some olive oil. The cold roasted chicken was fine, and so were the potatoes and artichoke. The lack of salt was galling.

Beard looked over the documents Pathé had given him, at the long list of aliments interdits. No olives, nuts, avocados, fermented cheeses, cabbage, or onions. Eggs were to be eaten boiled or poached, but never in an omelet. Goodbye clams, scallops, and mussels—all shellfish, in fact—goodbye croissants and any sort of pastry. Nothing cured, smoked, spiced, or marinated was ever to enter his mouth: no salami, prosciutto, or goose liver pâté. There would be no sweetbreads, and no caviar, either.

Could he live like this? Forever?

And could anything be more ironic: the grand epicure, immersed in the sprawl of his monumental cookbook, conjuring the flavors of a lifetime’s worth of eating, reduced to such meager provisions? Here he was, in Provence, surrounded by recipes and tasting notes, and he was starving himself.

Nevertheless, he forged ahead. He had been working far too long on American Cookery—six years!—and needed to finish. The entire enterprise seemed to have gotten away from him somehow. The book was too big. It was overstuffed, encyclopedic—a victim of Beard’s voraciousness, his boundless enthusiasm, and his distractible nature (all the very same reasons he himself was too big—but he knew that). Did he really need to include recipes for cheddar cheese balls with pimientos; for chicken casserole with macaroni, corn, peas, breadcrumbs, and cheese; for sloppy joes? These were among what he co

nceded to be the “grotesqueries of American cooking,” which he had included for the sake of making an accurate record of his native cuisine. And indeed he had a certain affection for such unpretentious, practical dishes.

But now he was trying to finish, to corral his unwieldy manuscript, hoping that he had managed to outline a distinct and worthy national cuisine—a cuisine he considered to be on a path to contend with that of France, as he said, for “after all, France created French cuisine over centuries,” and of course America was still a country much younger than France. Yes, American Cookery had an everything-but-the-kitchen-sink quality about it, but the writing was modern and opinionated, full of personal anecdotes and insights. American food, in Beard’s telling, was endlessly variable and always evolving. Although there were gaps in the book—for example, he had offered only a nod in the direction of the new vogue for health food and organic produce—he had made the case for the existence of a national distinct cuisine, and recorded much of its history, and he knew it was now too late for second-guessing. The book was long overdue. What he had would have to do.

This much was also clear: he was trapped in a French diet clinic with an unfinished American cookbook, and both facts weighed on him in unbearable fashion. He needed to escape.

Fortunately, escape was coming, in the form of M. F. K. Fisher.

The small but rather pleasant apartment M.F. had rented in La Roquette-sur-Siagne was about a twenty-minute drive from Grasse. Lord had found it for her. It was just across the road from the grand estate, Les Bastides, where Lord and Bedford spent their summers. They lived in London the rest of the year.

The days there had stretched into weeks. The weather was sometimes rainy and chilly, but mostly windy, bright, and beautiful. “Heavenly,” M.F. thought. Birds sang in the olive trees, and now and then a frog would emit a pontifical croak. She rose early in the morning to write, while Norah went across the way to Les Bastides, to garden with Lord, the two of them planting bulbs under the trees around the big stretch of lawn and terrace behind the grand estate.

In their rented flat, Norah had taken the bedroom, and M.F. was set up in the living room. There was a small separate kitchen and a large terrace. M.F. hadn’t quite known what to expect when she’d rented the place the previous summer, sight unseen, based on Lord’s recommendation. “If you don’t like being alone at night, simply lift your voice slightly and Sybille and I will hear you,” Lord had written. The house was modest, clean, and quiet. It cost thirteen English pounds a week, including heat—a price in keeping with the genteel British atmosphere of the enclave. A local woman came three times a week to clean and do the laundry.

Lord was the “general handyman” for Les Bastides and for the rental apartment, too. It was rather embarrassing, M.F. thought, to have to ask for help so often, but it was a country house, and this was France. The butane ran out in the kitchen, for example, and M.F. and Norah did not quite remember how one went about replacing the tank, which, in any case, was locked in a cage to which Lord had the key.

Time slowed down. M.F. and Norah were reading and cooking, wandering into town in Lord’s VW Bug to shop for groceries and mail letters at the post office. Les Bastides was only a mile from the center of La Roquette, but traffic on the narrow country road was heavy and precluded walking. Other days, they drove to Mouans-Sartoux, the next town over, and ate lunch there. Or they sat in a café with Bert Greene, a friend of M.F.’s who was in the area for a few days. A large, tall man in his late forties, Greene was exploring Provence with a friend. He laughed as he described his newfound love of pastis.

Greene had cofounded The Store in Amagansett on Long Island, New York, a shop that sold pâtés, salads, soups, roasted meats, side dishes, desserts, and other high-end groceries and gourmet prepared foods for takeout. It was one of the first shops of its kind, opening in the mid-1960s and catering to an increasingly sophisticated crowd—yet another harbinger of the changes in American taste. People were watching Julia Child, they were buying cookbooks, and they had an appetite, too, for “carry-out cuisine”—convenient, freshly prepared leek tarts and chocolate mousses.

Evenings, the sisters crossed the road to Les Bastides for cocktails with Bedford and Lord. The estate belonged to Allanah Harper, a wealthy and highly cultured Englishwoman who in the late 1920s founded the Paris-based literary journal Exchanges, which had introduced French writers such as André Gide and Henri Michaux to British readers, and W. H. Auden, T. S. Eliot, Gertrude Stein, and Virginia Woolf to the French. Harper and Sybille Bedford were old friends who’d been crossing paths in London and Paris since the 1950s. For years, Harper had loaned a converted garage on her Provence property to Bedford and Lord—“adjoining studios, a pergola, a terrace, jasmine and honeysuckle, night flowering climbers, tree frogs, set in an olive grove” is how Bedford described it.

M.F. and Norah had known Lord since they were kids in the mid-1920s. M.F. had idolized her—a fabulously glamorous high school student, the popular girl with the bob haircut—those many years ago, when they were classmates at Bishop’s. Lord had also lived at M.F. and Norah’s parents’ house for a time, after she was expelled from Stanford for her wild behavior. Years later, in 1959, M.F. wrote a letter to Lord, recounting her teenage infatuation:

If I believed, as indeed I did, that you were the most dazzling exciting human being I had ever met, it was because I was caught in one of the same mushy, ignominious, and disgusting “crushes” that so bored me in others … It seemed right and natural that girls would be swooning all over the damned silly neurotic hotbed for you, and I could only admit that I was as bad as any of them.

Not that anything particularly romantic ever happened. But it was a formative relationship for M.F., an early and intense connection that endured for decades, and one that tied her, however peripherally, to the London literary set.

Bedford and Lord were an odd couple. Bedford was the dominant, domineering one—moody, gregarious, irritable, loud, impatient, all depending on how her writing was going. She’d emerge from her room “like a bear with a sore head” (Lord’s words), daring anyone to strike up a conversation. She was born in Germany and grew up in Italy and Spain, her father some sort of dissolute aristocrat and her mother a morphine addict. She wrote novels that were also memoirs, in a fragmentary style. A Legacy, published in 1957, was widely praised, including by Evelyn Waugh, although the New York Times reviewer Richard Plant decried the author’s insufferable snobbery: “With breathless casualness, she tells us of the Merzes of Berlin (extremely wealthy, Jewish, and quite old school, you know), whose daughter marries a South German Baron von Felden (very French, very devout, ma chère) and a few scandals befalling the Felden family after that Merz girl (what was her name?) has died in Davos.”

Such was the oeuvre: world-weary, aristocratic, dense with the romance of the interwar years, people dying tragically in Davos. Bedford was also a cogent and serious culinary expert, and proudly judgmental. She wrote about wine, and traveled frequently to attend tastings.

Lord, meanwhile, was frail and birdlike, with big eyes and hidden depths. She smoked nonstop but did not drink, as her doctors had forbidden it after years of alcoholism. She had a quiet voice and an ironical, faux-naïve way of putting things. She was also a writer—her new novel, Extenuating Circumstances, would be published by Knopf the following year.

She could be socially awkward: when Child met her a few years earlier, she wrote to M.F. afterward that she found Lord “strange and withdrawn. I remember asking her some innocent question about herself, such as where did she grow up or some such inanity—she just couldn’t answer, after hemming and hesitating, we managed to get the subject changed. Very odd, and one suffers for her.”

Nevertheless, Lord and Bedford had an active social life and saw the Childs with some regularity when both couples were in France, not to mention the rest of what Lord called the “closed cooking circle,” including Richard Olney and, in London, Elizabeth David.

The

food world was indeed a small one, both in Europe and America. Everyone knew everyone else—all of them drawn together by a shared reverence for “the good life,” and there was indeed a sense of “closed-circle” exclusivity about it. With who else, after all, would it be worthwhile to discuss the merits of a particular preparation or vintage, if not a fellow connoisseur? But of course, petty rivalries and rampant snobbery were all the worse in such insular society. Nora Ephron’s “Food Establishment” article had made that very point.

Elizabeth David and M.F. were considered rivals of sorts—both of them seen as competing for the title of the most literary of food writers—even though they’d never even met. (David’s seminal A Book of Mediterranean Food, published in 1950, described the pleasures of garlic, olive oil, and Parmigiano-Reggiano, among many other things, for readers in postwar England.) Lord told M.F. a long anecdote about seeing David in London. “We had two dinners—at her house with superb wines which kept us sitting until the small hours, and another evening with her at a restaurant, on us but of her choosing,” she said. “I like her enormously, but I’m always mystified how time drops away when one is with her.”

Lord’s description of those dinners amounted to a bit of subtle social gamesmanship—name-dropping couched in carefully inscrutable phrases that may (or may not) have been intended as insults: the restaurant “on us but of her choosing”; the mystifying way (was that good or bad?) time dropped away in her company. Indeed, Bedford and Lord were experts at this game, and M.F., when she wanted to be, was no slouch, either.

More uncomfortably, Bedford and Lord also asked after M.F.’s daughters, Anna and Kennedy, in an ostensibly affectionate but unmistakably disapproving manner. Not that they disliked the girls, exactly; they just expressed wonder at the general neediness of even grown children. They were aware that M.F. had struggled in recent years to balance her life as a writer with her role as a mother of two young women. Neither Bedford nor Lord had children, so how could they understand? They couldn’t. Nevertheless, they had found a sore spot, and they poked at it.

Provence, 1970

Provence, 1970