Provence, 1970 Read online

Page 8

The show was now being broadcast in color, nationwide, Wednesday nights at eight o’clock—“primetime,” Paul noted in letters to friends, using quotation marks to signal a bit of amusement at the breathless TV jargon he’d taken to using. The truth is, he loved it—not the jargon but the thrill and speed of the medium, the technical details. Going from black and white to color, he would explain, required the use of much stronger lights, which in turn required Julia to wear special makeup; the editing, incorporating scenes of Julia filmed outside the kitchen, required split-second precision. They had filmed many of these scenes the previous summer in France, at open-air markets, or visiting with butchers, bakers, and restaurateurs. Paul handled the logistics, as he always did.

Paul and Julia were a team. She was the unforgettable performer, larger than life, no-nonsense, and he was the elegant and articulate partner, an artist and photographer. They shared life in ways few couples do, from the planning of the shows and the cookbooks to the social swirl of Julia’s celebrity. They had never had children, much to her regret, and so their emotional life together played itself out largely through her career.

France was at the heart of it all. The food they had discovered all those years ago—the sheer, stunning quality of it, the pleasure it represented—was what inspired Child to this day. She had taught Americans to cook, to appreciate the slow and careful simmering of a bœuf bourguignon or the proper composition of a vinaigrette. But the classic style of cooking that Mastering I and II represented had begun to hold less interest for her, and even feel a little constricting. In part, the sentiment was just a reflection of her impatience with Beck. It had been a long and contentious year for the two of them.

The final deadline for Mastering II had been in March, and for weeks leading up to that date, Child had shut herself in her office in her Cambridge house, writing furiously seven days a week.

She did all the writing, which meant that she did most of the work—understandably, since the book was in English, its audience American. Together, she and Beck worked out what recipes to include and tested them repeatedly, sending drafts and cooking notes back and forth across the Atlantic for the multiple revisions; but it was Child who made sure that, in the end, the recipes were replicable in America, that they made sense, and that they worked. Beck, on the other hand, felt it was her responsibility to ensure that the recipes were suitably French, and therefore authentic. She was a marvelous and intuitive cook. Indeed, many of the recipes originated with her. But Child knew that measurements, precise lists of ingredients, and clear explanations of timing were not Beck’s forte. She didn’t seem to understand just how time-consuming every revision turned out to be.

So there were inevitable conflicts.

There was, for example, the question of the Porc Braisé au Whiskey. Beck had sent Child the recipe and proposed adding it to the meat chapter, which contained only one pork recipe, for a roasted suckling pig. Beck had taught the braisé preparation at her various cooking classes and knew the recipe was a good one.

The problem was that they were out of time. This was another one of those things that Beck just couldn’t quite understand, perhaps because she was an ocean away, in France: they were at this point already deep into the copyediting stage, with the schedule so tight that the text was being sent off to the printer for typesetting chapter by chapter, as soon as the copy editor finished each one and Child reviewed the copy editor’s work. Adding a new recipe now would be insanity. And it wasn’t just the pork recipe, Child knew: Given the chance, Beck would be adding and refining and arguing about recipes forever. She was the keeper and protector of French food. She would never be satisfied.

Child responded diplomatically, but firmly: “I have only 5 weeks before the final final deadline, and so much to do I am stopping bookwork (recipe writing) on March 15th, no matter what is lacking. I have just had enough of this seven day work week and no respite. No more books of this type, and that’s final. Life is too short and we are getting too old!”

Beck then wrote a long letter in French to Judith Jones at Knopf, explaining her disagreement with the “adorable” Child. Beck asked Jones to please keep the letter a secret, and then described in great detail the precise merits of the pork recipe, the various people she had served it to over the years, how it was equally good hot or cold, and so on. The pork recipe currently in the book, she continued, was really “very poor.” She proposed that Jones, if she agreed that the braise was worthwhile, should “say to Julia that you think the chapter with the tripe is a little bit short, and ask her if by any chance she has another recipe to complete it? See what she says.”

Jones was the intermediary, soothing Beck and encouraging Child, and generally acting as psychologist, coach, sounding board, mediator, ego manager, and cheerleader. She understood the pressure Child felt as well as the frustrations Beck expressed. Beck had been sidelined a bit by Child’s success as a TV star; she was the coauthor of a book everyone thought of as Child’s, and that had to be hard to take. So it was no wonder she kept poking at and perfecting the recipes—she was holding on to what remained of her authority.

Jones responded to Beck’s charming and relentless scheming about the Porc Braisé au Whiskey with a charming and diplomatic letter of her own. “The recipe I must say looks tempting and I am dying to try it,” she wrote. “But even if it were the most delectable thing in the world, it is too late at this point to hold up the chapter which is already in copy editing and due at the printers next week.” She went on to ask a series of probing questions about the recipe, questions they did not have the time now to resolve—“How does ½ cup of bourbon and ½ cup of brown sugar make sufficient juice? You do say add bouillon, but how much?”—before concluding, “We could go on another year, but I think we all feel that would be foolish because there is plenty here for a fascinating book and you both want to get it out of your hair. It is hard to know how to help Julia because so much of the final burden does fall on her. But I am convinced one way we can both be helpful is not to argue about the details and specific recipes because it only uses up time and energy which she can’t afford at this point. I hope you understand.”

Of course she understood, Beck replied, she understood “parfaitement,” and she thanked Jones for explaining Child’s point of view.

Child, meanwhile, continued to receive recipe notes and revisions from the prolific Beck, but she had had enough. Never again, she swore, would she write a cookbook of this all-encompassing sort, and certainly not with Beck. Their friendship was forever, but the partnership was at an end. The rigidity with which Beck insisted on the most orthodox and tradition-bound aspects of French cooking had worn Child out. They had known each other since 1951, when they met in Paris and took cooking classes together, and almost immediately began working on a cookbook—the first Mastering. They had spent uncountable hours in the kitchen together over the years, but as a coauthor, Beck was simply impossible.

“Ma chérie,” Child wrote,

you have done ta mauvaise habitude of wanting to change everything in the recipe as soon as you have seen it again … you had this same recipe for le success, February ’69, and you reported that everything was just fine … I am therefore not going to pay too much attention to this letter, because I am sure when you see the recipe again (were it changed as you have directed) you would say NON NON NON—ce n’est pas correct, ce n’est pas français!—and as often happens … it is your very own recipe (that you have forgotten about) that you are now attacking.

No, there would be no further collaborations with Beck. Child would strike out on her own. What she would do, she was not yet sure, though she did have some ideas.…

Child could feel a shift in the balance of the food world. Top American restaurants, French and otherwise, were getting better, while in France, the grand three-star icons—Véfour, Bocuse, Troisgros, Oasis—were now big businesses, but “not really temples of gastronomy in the old sense” anymore, as she had written to M.F.

the previous summer. They had lost a bit of their magic.

Shopping for groceries in France, on the other hand, remained an unmatched delight. The open-air fruit and vegetable markets (even in winter) with their farm stands; the charcuteries, butchers, fishmongers, bakeries, and cheese shops—these were the places that inspired Child. She had made sure to include her favorites in the filming for the show, presenting tantalizing views of Old World food craftsmanship in full color. An olive oil press in Opio, just down the road from La Pitchoune; the fish market in Marseille; cheeses at Chez Androuet in Paris. She wanted to show her audience the authentic methods, products, and ingredients of good cooking. She knew this was no exercise in futility, for there were growing numbers of good markets, cheese shops, and specialty food purveyors back home in the States. There was even decent bread to be found, however rarely. M.F. had just sent the Childs a letter saying she had discovered the “best bread” in America, at a bakery in Sonoma, not far from where she was building her new house.

Now, in France, Julia could sense that some of the artisanal skills she and Paul had documented were slowly disappearing. There seemed to be ever more American-style supermarkets, for example. But she didn’t want to worry about that now: they were here, where it had all begun, la belle France. In a letter to M.F., Julia described the feeling she always had, upon arrival, of being “re-imprisoned by nostalgia and present pleasure.”

That line captured the mood, and not only of the Childs. M.F., Beard, Judith Jones, and Richard Olney had all been originally inspired by France, one way or another, and had changed American tastes with their passion. But this was a moment of looking forward as much as looking back. Change was in the air.

The next day, Beard and M.F. stopped by to say hello. The Childs loved seeing their two friends together: it was the Childs, after all, who had brought them together a few years earlier. “And that dear Mary Frances, whom we have not seen for too long a time—she likes you very much indeed, we know, from her letters,” Julia wrote to Beard earlier that year. “And wonderful you have met at last, the way you should have long ago. She is rather shy, however.” To M.F., Julia wrote, “Indeed, Jim Beard adored you, said he knew he would, and felt that it was only fate that had kept you apart.”

They were an odd couple: the effusive, gregarious Beard and the sly, acerbic M.F. They got along brilliantly.

It had taken Child herself a while to warm to M.F. During their collaboration on the Time-Life cookbook in 1966, Child thought M.F. indulged in a sometimes overly poetic, precious take on France and French food. “We who do not live in France might try adapting the good things in French provincial eating to our own potentialities, and our own conditioned hungers,” M.F. had written. “We can find good salad greens and good bread, and good cheeses and meats and vegetables if we want to. We can try to reach the slower pace of older habits than our own new nervous ones, by serving a small, tasty course at the beginning of a meal, before the main dish, and then skipping the gelatin pudding or ice cream.”

Child read the manuscript before publication and sent a letter to M.F. with her notes, expressing “an overall feeling that the French are over-romanticized and the Americans underestimated, as though France was seen with loving pre-war eyes, and America viewed from the superhighways, with every once in a while a meal with the TV-dinner set.”

But M.F. was in fact far from saccharine, or fuzzy-minded, as Child soon realized. The two women struck up an affectionate, witty correspondence, and so did M.F. and Paul Child. M.F. immediately understood his importance to the entire Child enterprise, including the books and the show. Not everyone realized or saw that.

“One reason we are friends,” M.F. wrote to Julia in late August 1970, “is that we both understand the acceptance of NOW. There is all the imprisonment of nostalgia, but with so many wide windows.” The topic was France: its inevitable centrality in their lives, the site of their common awakening to taste and sensation. But they must not let the past overshadow the present, they agreed, for France was changing, and they both understood that they must, too.

M.F., a modern master of memoir, of the revelatory personal essay, was paradoxically but assertively anti-nostalgic, always looking for those “wide windows.” This unsentimental toughness was in many ways at the core of her genius as a writer. It also bound her to Child, whose insistence on practicality and modern methods had led her into conflict with Beck’s old-fashioned, this-is-how-it’s-done-in-France (and how-it’s-always-been-done) certitude.

The previous year, as she was working on the Mastering II manuscript, Child had read an article in a French magazine that included the line “Every Frenchman is convinced he is a connoisseur who has nothing to learn from the experts.” She pointedly sent a photocopy of the article to Beck, and also to M.F., whom she addressed in a note in the margin, saying that this French trait was “exactly what has been bugging me in my collaboration, and why I can’t take any more of it. I don’t know why I have been so dumb, but it is something one can hear, but not feel viscerally because how can anyone (but the French) have such arrogant nonsense as to live by that conception.”

The Childs, M.F., and Beard stood on the terrace at La Pitchoune in the cool December air. There was a faint scent of smoke—leaves burning somewhere in the distance, the smell of late fall turning into winter. Beard was genial, as always, but he looked weak and unsteady. His stay at the Grasse diet clinic had yet to produce the desired results in his health—or his weight.

The four friends went inside, entering through French doors into the living and dining room. The high-ceilinged space was simply furnished—there was a large, round dining table by the window in the back, and a massive fireplace.

Paul poured glasses of wine, and they discussed plans for the coming week.

When were Judith and Evan Jones arriving, and wasn’t Richard Olney coming to visit soon, too? M.F. described the elaborate dinner Olney had made for her, Bedford, and Lord a few weeks earlier, in his beautiful house on a very steep hill. There were more dinners to plan and excursions to look forward to. Simone Beck and her husband, Jean Fischbacher, had arrived the previous week, the Childs said—they were arranging an elaborate New Year’s party at Le Vieux Mas, just across the way from La Pitchoune. M.F. and Beard had been tooling around the countryside together in recent days and had made a plan to visit Vence and Saint-Paul-deVence soon, to see the Matisse chapel and the Maeght collection.

Perhaps the four of them could drive over to Biot one day next week, Julia proposed. There was a nice little restaurant they could stop at for lunch on the way back. And M.F. and Beard must both come to dinner on Sunday, the Childs said, and bring Lord and Bedford.

There was a special pleasure in seeing friends in foreign places, out of context, away from America. M.F. sent the Childs a note the next day. She could have telephoned, but preferred the less intrusive intimacy of writing. It was in pencil, and scrawled across the top was an apology: “Sorry about the pencil—all 6 Bics have frozen at the same time!” The winter was turning cold.

Dec 11, 70

Chers amis—I am very happy and serene about having seen you yesterday, and there, and with that dear man. And it will be nice to come on Sunday with Eda and Sybille. I’ve never gone with them to another house! (And only once to a restaurant.) …

I’d like very much to have lunch with you and Jim Beard on Wednesday. Carpe diem. Would you like to come in for a vermouth or something? This is a pleasant little pad.

Love, MF

7

JAMES BEARD’S DOOMED DIET

CELEBRITY DIET DOCTOR GEORGES PATHÉ’S offices were in the discreet Villa Fressinet, on the outskirts of Grasse. From the windows, there were views of the valley below stretching into the distance—Grasse was set on a mountainside overlooking the rolling Provençal landscape. The medieval town was pretty, and had long been the center of the French perfume industry, with greenhouses and flower fields and numerous perfumeries.

In an examining

room at the clinic, James Beard was having blood drawn. The doctor had noted his swollen legs, listened to his heart, and palpated his stomach. They were running every imaginable test, on every imaginable substance and molecule that might be found in his blood, urine, or anywhere else. There were electrocardiograms and abdominal X-rays. Pathé was an expert in diabetes and other endocrine diseases, and he was thorough.

Beard handed over a letter from his doctor in New York. It was typed on letterhead:

To Whom It May Concern:

Mr. James Beard requires reduction of weight and improvement in lower extremity vascular condition.

He is in good health except for mild cardiac disease for which he takes digitalis and hydrodiuril.

Sincerely,

John E. Sullivan, M.D.

Pathé asked Beard to step onto the scale. He weighed 138 kilograms—304 pounds. It was clear that Beard was significantly overweight, but Pathé took a holistic approach, knowing that the weight was only part of the problem. He asked Beard about his life and career, his work as a writer, his expertise in food and wine, the many long and exhausting trips he was obligated to take—consulting for restaurants, attending conventions, judging cooking contests, evaluating the in-flight menus for an airline client, and so on. Pathé tried to explain the relationship between Beard’s weight and his health and well-being, his heart in particular. It would not be enough, he said, for Beard simply to go on a diet, to submit himself to Pathé’s low-calorie regimen for a few weeks, and to lose a few pounds. No, he needed to change his life. It was a question of free will and choice, Pathé said—Beard alone could achieve a “moral victory” over his obesity.

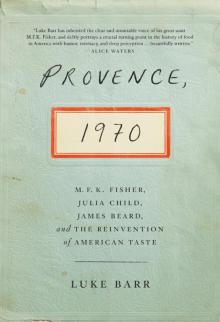

Provence, 1970

Provence, 1970