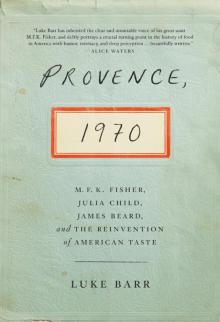

Provence, 1970 Read online

Page 11

This was a rustic-seeming dish, the broth twice cooked, once with oxtail and once with beef shank. The process was laborious, and the goal was to highlight the essential, transcendent flavor of the meat and broth, presented in the earthenware cooking pot. Olney had served it in his tiny Paris studio, which smelled faintly of oil paint and turpentine. He wore “rags”—an unbuttoned shirt, paint-flecked pants. And so the Olney mystique was born. All the cooking was done in advance: he made it look easy.

9

A DINNER PARTY AT THE CHILDS’

IT WAS A SUNDAY EVENING IN MID-DECEMBER, and Julia and Paul Child were awaiting their dinner guests, M.F. and Beard. They had urged M.F. to bring her friends Eda Lord and Sybille Bedford, too. So they would be six.

Why had she bought such an enormous chicken? Child wondered. It sat on the counter looking rather larger, somehow, than it had at the butcher’s. She’d gone shopping that morning in Plascassier and Grasse, to the excellent Boussageon for meat and various charcuterie items, and to Madame Londi’s, her favorite fruit and vegetable shop. She found Boussageon’s pâté to be fine and carefully flavored. In Cannes the previous day, she and Paul had walked along the narrow rue Meynadier, with its many food and specialty shops selling cheese, chocolate, and macaroons; fish, game, and quiche; and of course an endless selection of Provençal dishware, gifts, and handbags. She ended up buying a smoked salmon that was the biggest she’d ever seen—almost three feet long!

She would roast the chicken and some potatoes, and set out some of the prepared dishes as appetizers, along with fresh bread. She would make a salad. This would be an easy dinner—a casual affair. There would be something simple for dessert.

James Beard arrived early and was soon poking around the kitchen with her. He would make a soup, he said. He began washing and chopping a large amount of chard he had found in her refrigerator.

Child and Beard loved cooking together, and had even given themselves a joint nickname a few years earlier: Gigi, a combination of their names (or at least, the Js in their first names, as pronounced in French). It was silly, of course, but that was the point. The Gigis are in the kitchen, they would say. She wore a bright flower-patterned dress, and he had matched her with an equally colorful bow tie.

Child trimmed the fat from the extra-large roasting chicken, ran it under the cold faucet, and then dried it off with paper towels. She and Beck had disdained this practice rather imperiously in the first volume of Mastering, but had recently changed their minds, deciding it was a necessary precaution against bacteria. She rubbed butter and salt inside the bird, and then began to truss it with a great length of kitchen string and a large needle. She was an elaborate trusser of birds, tying up the legs at one end and the wings at the other.

She rubbed more butter on the outside of the chicken and then arranged slices of fresh pork fat over the breasts and thighs, and tied them in place with more of the string. She set the very secure-looking bird in a large oval roasting dish and put it in the hot oven.

Beard, meanwhile, was sautéing leeks and garlic in a large pot, for his soup. He was doing his best to keep up a cheerful countenance, but Child could tell it was a strain for him. He sat down frequently to rest his legs.

Child sliced potatoes for a gratin dauphinois, layering them in a heavy dish with plenty of cheese and butter, and then pouring hot milk over it. Into the oven it went, next to the chicken, which she took out to baste and to turn on its side. Her method for roasting chicken involved multiple shifts in the bird’s position, so it would cook evenly and brown all over, and lots of basting. She added carrots and onions to the bottom of the dish, to enrich the sauce.

Paul went to collect some wine for dinner. They had determined that digging a proper wine cave would be preposterously expensive, so they kept their bottles in a cellar-like room beneath the cabanon—the small, one-room stone structure across the driveway where Paul had his painting studio. It had a window looking over the valley.

The sun was setting and the sky was dark as Paul, bottles of Bordeaux in hand, heard Eda Lord’s VW Bug sputtering up the steep unpaved driveway. He waved as Lord pulled in next to his rented Renault. She emerged with Bedford and M.F., all of them shutting doors and calling hellos.

Julia opened the side door directly to the kitchen, and she and Beard welcomed them in. Paul took the corkscrew from its hook on the Peg-Board kitchen wall and opened the wine. The kitchen smelled wonderful, and they all offered to help—arranging some of the smoked salmon and pâté on plates, setting the table, stringing beans. Dinner at La Pitchoune was a communal affair. Julia presided in the kitchen in her apron, towering over her guests. Everyone pitched in.

Beard’s soup was simmering on the stovetop, the improvised chard and tomato soup, with various other tidbits tossed in. Child gleefully dubbed it the “Soupe Barbue”—the “Bearded Soup,” after its maker.

The mood in the kitchen was very different at La Pitchoune than it was at the Childs’ house in Cambridge. At home, Julia ran a working kitchen: Recipes were tested, alternate ingredients and methods were tried out, nothing was left to chance. The contents of her two refrigerators were carefully indexed and posted on their doors. There was evidence of her rigorous process everywhere you looked—competing versions of the same dish cooling on the counter, recipe notes and annotations stuck to the wall. “Put it to the test” was the spirit of the place.

Provence, on the other hand, was a free-for-all. No one was overly self-conscious: “Will Julia approve of this vinaigrette?” was not a thought that crossed anyone’s mind. The kitchen was a happy, casual, slightly tipsy melee—chaotic fun. Paul poured more wine. Everyone seemed to be talking at the same time.

Was there a better smell in the world than a chicken roasting in the oven? The slowly crisping skin, the sizzling noises reaching a crescendo. Julia had removed the pork fat for the final browning, and now she proclaimed dinner ready.

PTÉ DE CAMPAGNE AND SMOKED SALMON

“SOUPE BARBUE”

ROAST CHICKEN

GRATIN DAUPHINOIS

HARICOTS VERTS

SORBET

The round table was set in the main living room, the pâté and smoked salmon at its center, and Paul was cutting up a baguette. There was a fire crackling in the large fireplace. M.F., Beard, Lord, and Bedford began to arrange themselves at the table, carrying their wineglasses. In the kitchen, Julia took the bird from the oven to let it rest a bit before carving. To make sure it was completely cooked, she cut into the leg.

Quel désastre! It was bloody!

“You’d think,” Julia said, laughing, “that I’d know how to cook a chicken by now!” Well, it had been an exceedingly large chicken. It would go right back into the oven.

M.F. and Beard laughed. Paul pretended to be irritated—the delay meant he’d have to open more bottles of wine. He went out to the cabanon to replenish supplies.

At dinner, half an hour or so later, they talked politics and food. Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia was bemoaned. The quality of the local ham and salmon were celebrated. The wine was praised.

Bedford was mostly in good form, M.F. thought—thank God, as she could be boringly difficult sometimes, especially when it came to discussing wine. As for Lord, she was quiet and enigmatic, as usual. Julia and Paul were relaxed and happy, and Beard seemed cheerful, though his health was on everyone’s mind. “We worry about him,” Julia wrote in a letter to M.F. the following week. “The sight of those mahogany legs that one glimpses between pant cuff and sock are frightening. He seems depressed, although manages to hide it—and no wonder. What a dear and generous friend he is. One can only pray that he will manage.”

Privately, Julia and Paul thought the situation was dire: “Our dear fat friend is on his way out,” they said to each other. “We must steel ourselves.”

M.F., meanwhile, found herself contemplating the design of a special chair for Beard, on small, silent wheels that would allow him to move around, upright, without burdenin

g his overworked legs—“zipping deftly here and there behind the counters in his kitchens, still taller than anyone.”

The “Soupe Barbue” was a hit—the rich sweetness of the chard and leeks set off by the acidity of the tomatoes. And it was healthy, too, Beard insisted, made with a minimum of olive oil.

He was allowing himself to eat dinner, despite the forbidden nature of certain items—Pathé would never know about the bites of pâté or smoked salmon, nor the glass of wine. Or two. Beard was nearing the end of his stay at the clinic anyway.

There was gossip, talk of mutual friends, of new restaurants in Paris, New York, and London. Beard’s old friend Joe Baum had been ousted from Restaurant Associates, the struggling New York company that ran the Four Seasons, Tavern on the Green, and many others. But Baum had just landed a plum consulting contract to create the restaurants at the World Trade Center towers, currently under construction. One of them would sit at the very top of one of the buildings and be the highest restaurant in the world.

Bedford and Lord realized they and Beard had a London friend in common: Elizabeth David, who’d recently sent Beard a letter from Italy:

I thought of you today while having lunch in a real Tuscan tavern in a place called Colle Val d’Elsa, such good, authentic food, and perfectly delicious roast pig, very delicately flavored with wild fennel and cooked perfectly—how you would have enjoyed it, and how rare this sort of food and this type of restaurant have become in Tuscany. It’s been disappointing this year. Indifferent wine everywhere and not very interesting food. But the countryside is divinely beautiful in October.

Was good, authentic food getting harder to find in France as well as Italy?

David certainly thought so, Beard reported, but then, she was a gloomy sort, her small London kitchen shop in perpetual semi-crisis, her writing slow and arduous. She was working on a bread book and making little progress, and referred to her just-released Spices, Salt and Aromatics in the English Kitchen as “a squalid little book.” From London, David wrote that chef Bill Lacy’s new restaurant (called Lacy’s) was getting great reviews: “I’m very pleased for Bill—but somehow I can’t bring myself to go and eat there. The food is just restaurant French food—or perhaps it’s improved by now—if only one could go to a French restaurant and get a cup of beautiful consommé followed by just one authentic dish not fussed up with a lot of extra vegetables—and above all not heated up. I wonder if I will ever get back to Lucullus in Avignon to eat that fish soup.”

Bedford shared her friend David’s attitude of dismissive hauteur toward banal “restaurant French food”—her term for what Richard Olney called “Grand Palace” and “international hotel cooking.” She was a purist, and yes, she felt the same way about consommé. She, too, adored Hiély Lucullus, with its Art Nouveau–style, second-floor dining room near the Place de l’Horloge. It had been there since the 1930s.

This they could all agree on: Hiély was a classic place. Unchanged and unchangeable, and with an admirable fish soup. M.F. had eaten there countless times over the years.

But today, Bedford now continued, there were too many restaurants serving reheated roasted meats wrapped in pastry, sauces thickened with corn starch, and various ridiculous flambés. It was theater, not cooking—it was, no offense, the Americanization of cooking.

They all laughed.

But Child was quick to retort: there was mediocre food all over. And in fact it seemed to her that even many of the great three-star French restaurants had been overly commercialized, made to run like mechanized assembly lines, at the expense of some of the craft and skill—“hand work,” she called it—in their kitchens. She strongly disagreed with the New York Times’ Craig Claiborne, who’d recently written that no American restaurant could touch France’s greatest. She’d been to all of those so-called “greatest” places—indeed, Paul had gotten food poisoning the last time they went to Le Grand Véfour in Paris.

“I have eaten every bit as well in New York,” she declared.

Child liked and respected Claiborne, but he was a snob. Earlier that year, she and Paul had written him a letter to protest his veiled, smirking criticism of Henry Haller, the White House chef under LBJ and now Nixon, a president “widely reputed to have a predilection of some sort for cottage cheese garnished with catchup,” as Claiborne wrote. The Childs had no love for Nixon, but the Swiss Haller, an acquaintance of theirs, had nothing to do with the food made in the private quarters of the White House. He cooked state dinners, and he was, furthermore, a damn good chef, “doing his best to show the world that this is not a nation of uncouth hicks gastronomically,” the Childs wrote, with some feeling. Julia herself bore no small amount of responsibility for the 1960s democratization of taste and cooking in America, and she took her role seriously. Hence the letter to Claiborne.

Child’s aversion to snobbery was deeply ingrained, reflected in her whole persona, her slightly comic, encouraging patter on television, her no-nonsense practicality, her warmth. The antipathy had only become stronger over the years, probably never more so than this year. The collaboration with Beck—la Super-Française—had exacerbated and magnified the feeling. It wasn’t just her coauthor’s repeated declarations about correct and proper French cooking traditions; it was the righteous, Olympian authority with which she delivered them that was so maddening. And the same was true of Claiborne, so sure of the superiority of the grand old French restaurant institutions, and of Bedford, going on about consommé and the Americanization of cooking.

Child was ready to turn the page on the retrograde attitudes and old-fashioned ideas.

American food was changing, and she was ready to embrace that change. She was finally done with Mastering the Art of French Cooking—two volumes were quite enough!—and preparing to move in a new direction, whatever that might be. Rather than pine for the old days of consommé, she welcomed the beginnings of a more globalized, international food world. She could see herself branching out to New England chowders and Indian curries, to Italian pastas and Chinese sauces and marinades. Like Beard, she understood that American food was starting to embrace more ethnic traditions, and she was eager to explore them. She was also eager to write in a more informal, casual way, freed of the Mastering books’ cooking school master class style. Of course, her cooking would remain French-inflected, but the TV show and cookbooks would allow her to spread her wings.

Was it Beck who had held her back? With her distinctly French sense of superiority? Her unspoken jealousies? Beck could never quite believe that any American could cook French food properly, and Child’s identity as the TV’s French Chef seemed to Beck a moral affront.

M.F. was now recounting an amusing day she had spent with Beck a few weeks earlier. She had dropped by Le Vieux Mas, next door, for an afternoon visit.

“Simca: quelle femme!” M.F. said. Beck had been full of talk and authoritarian vigor, so “energetic-firm-bossy-bitchy-forceful that one is cowed by her!”

Child knew just what she meant.

“I liked her, at home,” M.F. continued. “But I’d sure as hell hate to cope with her in Paris or New York. Sit here, eat this, drink when I say—not any choice. Ah well.”

Paul and Julia nodded knowingly. Exactly. Simca and Jean were in Paris at the moment, so the Childs hadn’t had to invite them to dinner tonight. They would see them soon enough, over Christmas.

Child carved the chicken and carried the platter out to the table. It was most certainly done now—but not overdone—and they all laughed again at the delayed start of dinner. The chicken was perfect, and so was the gratin, and so were the beans. They passed plates and dishes, and poured more wine, toasting each other, good fortune, and France.

It was remarkable, M.F. thought, how different this dinner was in spirit to the Olney dinner a few weeks earlier. The food was far simpler, of course, something like a family dinner. This was Child’s kitchen, but they had all helped cook, however haphazardly. It had been fun. M.F. had liked Olney, and admired

and enjoyed his brilliant, meticulous cooking. But the priestly high seriousness of it all had worn thin that night. Having long ago escaped America in order to discover France, she was now wondering if she needed to escape France to find herself. On the other hand, was this not where she belonged? It was here that her philosophy had been born: her insistence on pleasure, on the significance of ephemeral moments. She drifted back and forth between her thoughts and the conversation going on around her.

Bedford, God help them all, was now droning on about wine, and Paul was nodding patiently.

M.F. and Beard were soon in the midst of a discussion about the intriguing appeal of fresh green peppercorns—poivre vert—the ingredient of the moment, they agreed. M.F. had bought a supply at a local shop, La Grassoise, to bring home, and Beard’s friend and collaborator José Wilson was already scoping out possible recipes back in New York.

Lord was mostly silent.

As they ate, Child asked M.F. about her new house in Sonoma County. It was progressing slowly, but well, she said, and they must all come and visit when it was done. True, it was in California and not Provence, and she’d had to say a “sad, grim No” to her dream of terra-cotta tiles like the ones here at La Pitchoune; they were too expensive. She was having all her shabby but beautiful rugs cleaned, however, and they would look very nice indeed.

They all agreed to visit her in California—they’d come next fall, the Childs said. They’d be out in San Francisco at some point, certainly, and Glen Ellen was only an hour and a half’s drive north. Julia and Paul’s Cambridge house was also being worked on—the noisy and dusty work was happening now, in their absence.

Talk turned inevitably to the overdevelopment of the Côte d’Azur. Too many new villas and too much traffic, Paul decreed. Of course, the problem was money: there was too much of it! M.F. said she’d gone only yesterday to visit an old friend, Larry Bachmann, and his wife, in the hills high above Cannes. Bachmann was a successful movie producer (and long-ago lover), and the newly built house was the most stylized modern one she’d ever seen, she said—“amazing, quite beautiful, completely impersonal, just like its owners. Black living room ceilings about 30 feet high—walls of glass—bathtubs out in the middle of rooms, silent manservants slipping about.”

Provence, 1970

Provence, 1970